Turning the Hull

Turning my boat hull for the first time was an adventure—unexpected challenges, a failed pulley, and a hard-learned lesson in securing loads properly!

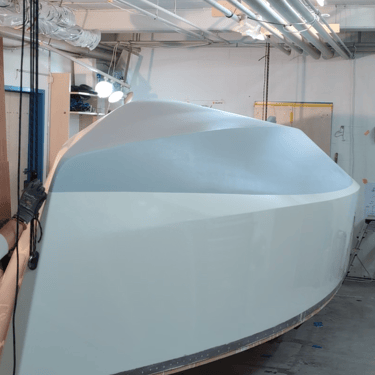

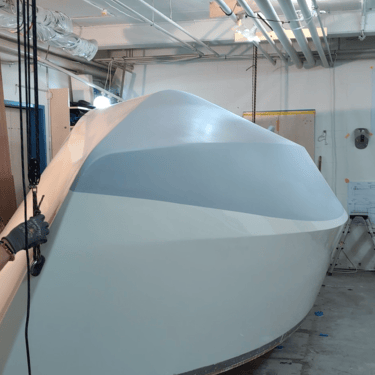

I started the New Year 2025 by turning the hull. I wanted to replicate the method used by Christian Sauer (Hull #103), which I believe I saw on Facebook. The idea was to create two attachment points, one at the bow and one at the stern, to hoist and then rotate the boat.

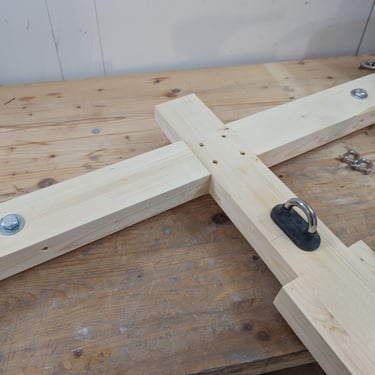

Since my boat was at its lightest—without Frame S or bunk sides installed—I estimated its weight to be no more than 500 kg, excluding the strongback. To build the pulley system, I decided to use Blueshark violin blocks from the backstay. The first three pictures show the pulley setup and the components used. The weakest link in the system was the Blueshark blocks, rated for a working load of 410 kg.

For the pulley system at the stern, I built a mount that could be bolted onto the transom. The two lower holes were positioned where the cockpit drains would be, while the upper ones aligned with the future upper rudder hinge. The U-bolt was roughly at the same height as the one on the bow.

At first, the hull-turning process went well. Lifting took some effort since the pulley provided only a 1:4 mechanical advantage, and overcoming the initial friction in the blocks required two people—one operating the pulley and another assisting at the boat. Once the boat was slightly suspended, I crawled inside to remove the strongback. Unfortunately, at that point, the GoPro decided to stop recording without any warning, which is why I don’t have more footage of the process.

While turning the boat, the aft pulley suddenly slipped, causing the hull to drop to the floor, smashing down onto the starboard aft corner and Frame C, which instantly snapped. Thankfully, no one was seriously injured. Joe from Hull #165, who was helping, got a minor cut on his hand from a sharp wooden edge. Unfortunately, my Drifting Donkey took its first beating.

Below are some pictures of the damage to Frame C and the failed Blueshark block. It’s clear to me that the teeth on the cam cleat had broken off, causing the rope to slip and resulting in the fall. I replaced the Blueshark block with a Lewmar block, which showed no signs of wear after successfully completing the flip. In hindsight, I should have secured the lines with a stopper knot or at least some half-hitches. Prior to the boat slipping, the cam cleat was the only thing holding the load, which was both dangerous and negligent on my part. I should have known better, especially since this wasn’t my first hull-turning.

I am still very disappointed in the quality of the Blueshark block. If it’s rated for a working load of 410 kg, the cam should also be able to hold that weight. However, it clearly failed under no more than 250 kg of static load. Considering that a boat’s backstay can easily experience dynamic forces much higher than that, this is concerning.

Note on Blueshark Cams: The remaining cams in the Blueshark package have been replaced with aluminum ones.

After the incident, we secured the boat, swapped out the failed block for the Lewmar one, and lifted the boat again—this time securing both sides with a stopper knot and two half-hitches. The rest of the turning process went smoothly, although the deck beam of Frame C would have been helpful to hold onto.

Overall, I think this is an effective way to turn a boat, provided you have secure ceiling fittings and at least three friends to help. Thanks Friends!😊

Lessons learned:

Use a larger pulley for better mechanical advantage.

Invest in higher-quality hardware.

Always secure the load properly.

I will be writing a separate post about the damage and repairs.